Abraham Lincoln, ranked by most historians and citizens as our greatest president, is the subject of  a book published in February 2015. Written by Richard Wightman Fox, a history professor at the University of Southern California, Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History explores how Lincoln’s body fascinated Americans throughout his life and even after death.

a book published in February 2015. Written by Richard Wightman Fox, a history professor at the University of Southern California, Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History explores how Lincoln’s body fascinated Americans throughout his life and even after death.

Interview with the Author: The following is an excerpt from an interview that Dr. Fox gave with the Huntington Library in San Marino, California about the book and about Lincoln. To read the complete interview, click here.

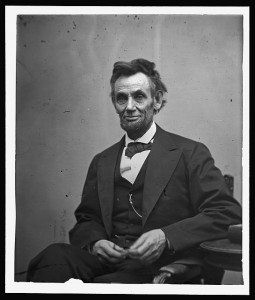

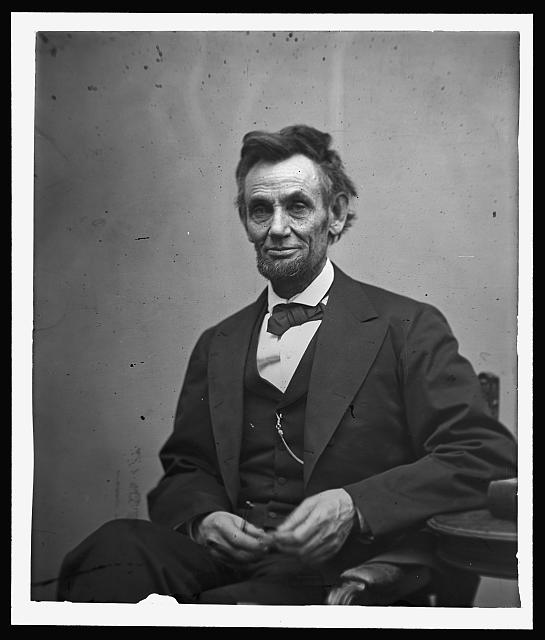

One of Lincoln’s Last Portraits | Huntington Library: Your frontispiece features one of the last portraits of Lincoln, a photograph by Alexander Gardner that accentuates his weather-beaten appearance.

A Fatigued President | Fox: Photography emerged in the 1840s, just in time to preserve the look of Lincoln’s body over the last two decades of his life. In the 1860s, cheap cartes-de-visite made his image available to millions of northerners, and many southerners (including a few slaves) owned prints of his face taken from newspapers and magazines. Pictures like Gardner’s, bringing out his wrinkles and facial crevices, showed how fully he’d given his body up to the twin causes of union and emancipation. This Lincoln has been withered by the war years. By Feb. 5, 1865, the date of this photo, he appeared hollowed out.

A Satisfied President | Fox: Yet the Gardner photo registers satisfaction as well as fatigue. Lincoln conveys physical relaxation, and for once he almost smiles. We can’t miss his contentment. He doesn’t know when the war will end, but he does believe it will end with Union victory and the destruction of slavery. Less than two months later, as it turned out, he would be walking the streets of Richmond with his son Tad, surrounded by thousands of exuberant former slaves.

More Than Just a Funeral Story | Huntington Library: At one point you intended to focus exclusively on the story of the funeral procession—the literal movement of Lincoln’s body through the country by train. Why did you decide to expand the story, tracing Lincoln’s symbolic path all the way to the 21st century?

An Extended Period of Grief | Fox: Initially, I thought the story of Lincoln’s body would finish with his interment in Springfield, Ill., on May 4, 1865. But the more research I did, the more I realized that northerners and southern blacks weren’t done mourning for Lincoln just because the funeral journey had come to an end. Whitman made that point in his 1865 elegy to Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” His grieving for Lincoln, he wrote, would be repeated every spring, a perennial growth in his heart. Reflecting on Whitman opened me up to the reality that in early May of 1865 millions of Americans had just begun to experience and make sense of the loss of Lincoln.

Lincoln’s Lasting Legacy | Fox: For many blacks and northern whites, the feeling of bitter loss persisted for generations. They believed Lincoln had given his body up for them. They shared a profound love for Lincoln, but the intensity of that love created divisions, too, as Democrats and Republicans fought over the political meanings of his physical sacrifice.

Grief in the 19th Century | Huntington Library: You explain that people yearned not only for last words from Lincoln, but also a glimpse of his body. Was this typical of mourning in the 19th century?

No Last

Words From Lincoln | Fox: Nineteenth-century Americans wished for last words from their dying loved ones, and they wanted to witness those words being spoken at the deathbed. Lincoln died about nine hours after being shot, with a sizable group of friends and officials standing around his deathbed. But he’d lost consciousness at the moment of the attack, and there would be no last words.

Lincoln’s Virtual Last Words | Fox: The recent rise of embalming made it possible to put his body on display in city after city, so that citizens could bid him a personal farewell. And the people got busy creating a set of virtual last words. They went back to the Second Inaugural and pulled out the line “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” Newspapers published his favorite poem,“Mortality,” and they were so eager to bestow some last words on him that they often mistakenly claimed Lincoln had written the poem himself. (It was written by William Knox in the 1820s.)

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

YouTube

YouTube

Pinterest

Pinterest