Winning the Presidency involves an understanding of changing demographics and identifying constituencies likely to support a candidate. But it also involves campaigning strategically in key battleground states in order to win the Electoral College, which ultimately is who elects the President.

Changing demographics: The percentage of whites in the United States has been steadily declining over the years as the percentage of minorities, especially Hispanics, has been increasing. Candidates and political parties need to understand these shifting populations as part of campaigns and governing. In addition to racial changes, the population can be understood in terms of economics. In 2016, we have seen populist candidates appeal to the frustration of many voters with the complexity of our modern world and feelings of being left behind economically. The education level of voters is also a factor in determining which candidates they are likely to support. Religion and cultural beliefs is yet another factor in assessing the likely success of candidates. These demographic factors, along with others, has created extreme polarization among voters, and civil discourse is often at risk.

Electoral College: Beyond demographic issues, we remember that the ultimate winner of a presidential race is the one who wins a majority in the Electoral College, which was the Founding Fathers’ method of indirect election of the President. To win, a candidate must win a majority of the Electoral College or 270 votes. The number of electors per state is equal to the total of the number of Representatives and Senators. Most states award electoral votes based on which candidate wins the most number of votes in the state – a winner-take-all system. Only Maine and Nebraska award electoral votes by the winner of each congressional district.

Election of 1800: In the election of 1800, no candidate had a majority of votes in the Electoral College and Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr were tied. According to the Constitution, in such a case, the House of Representatives selects the president with each state having one vote. After seven days and 36 votes, the House finally selected Jefferson as the nation’s third president, with ten out of sixteen states casting their vote for the author of the Declaration of Independence.

Winning the popular vote, but losing the Presidency: In four elections, the winner of the popular vote lost the Electoral College, and therefore the Presidency:

- 1824: With four major candidates, no candidate emerged with a majority of the Electoral College. Andrew Jackson led in the popular vote with 41.4% and 99 electoral votes, which was not a majority. The election was thrown into the House of Representatives which chose John Quincy Adams, prompting Jackson and his supporters to allege that there had been a “corrupt bargain” in which candidate Henry Clay threw his support to Adams in exchange for being appointed Secretary of State.

- 1876: In one of the most controversial elections in our history, Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote with 50.9% to Republican Rutherford Hayes. But the election results, and therefore the electoral votes of three southern states were in dispute. Congress appointed an Electoral Commission to sort through the votes in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. The Commission voted on purely party lines and awarded all of the electoral votes from these three states to Hayes, who won the election with 185 to 184 electoral votes. The final decision on the winner wasn’t known until just days before the March 4, 1877 inauguration.

- 1888: Incumbent President Grover Cleveland won the popular vote with 48.6% of the vote, but based on which states he won, Republican Benjamin Harrison, the grandson of William Henry Harrison, our 9th president, won the election with 233 electoral votes to Cleveland’s 168 electoral votes. Cleveland returned four years later to defeat Harrison, and thus became the only president to have served two non-consecutive terms in office.

- 2000: Even though Al Gore won the popular vote by more than a half million votes, Republican George W. Bush ultimately prevailed in the drawn out election process that saw the results in Florida disputed. A U.S. Supreme Court decision that stopped a recount in Florida gave Bush a razor thin margin of 537 popular votes there, and with it Florida’s electoral votes. That put Bush at 271 electoral votes, one above the majority needed to win.

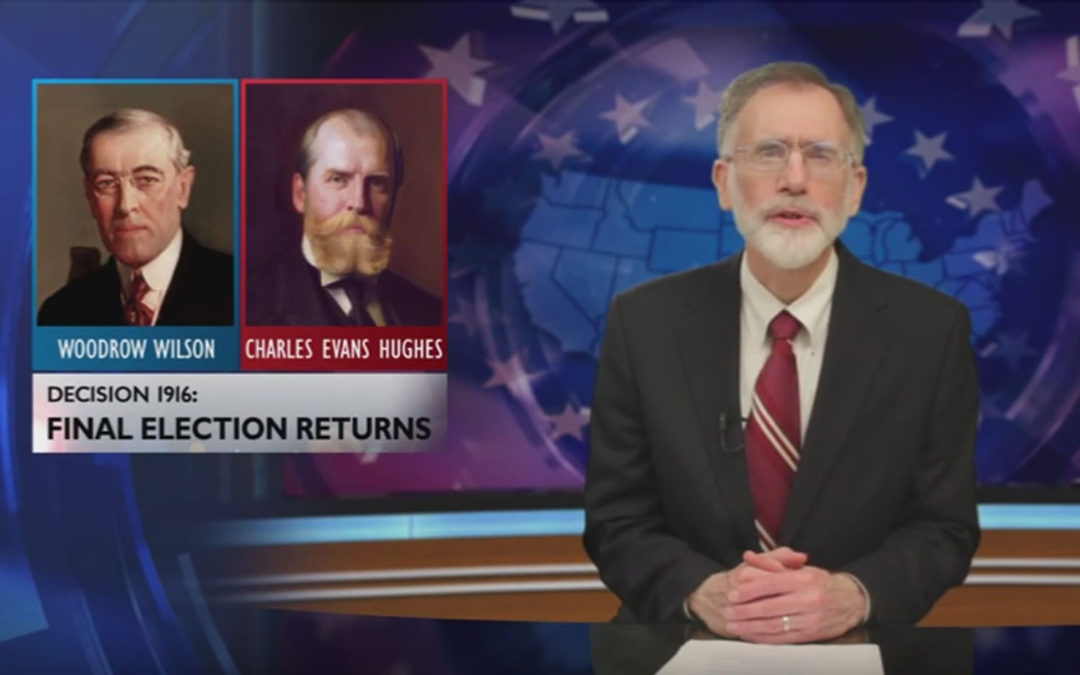

Close elections: Many elections, with the shift of just a few votes in some states, could have brought about either different results, or thrown the election into the House of Representatives. For example, in 1916, Woodrow Wilson’s margin for re-election hung on winning California by just 3,773 votes. Had those votes shifted to Republican Charles Evans Hughes, he would have won California’s 13 electoral votes, and with it, the Presidency. Click here to watch me report from the Presidential History News TV anchor desk as I cover the surprising shift of an anticipated win for Hughes to Wilson’s win when late breaking California returns finally arrived after being delayed by a snow storm. This short video is historically accurate and helps make history fun and accessible.

Lecture online: In a lecture on March 24, 2016 at the University of Puget Sound, I presented information about these and other key subjects along with my colleague, Dr. Michael Artime, a political scientist. The video of the lecture is available for viewing by clicking here.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

YouTube

YouTube

Pinterest

Pinterest