Since George Washington was elected our nation’s first president in 1789, there have been a total of 57 presidential elections. While there has never been a presidential candidate that has been replaced after their nomination, there has been one vice-presidential substitution. There have also been a couple of other quirks in the election process that could have caused a fair amount of commotion.

Before the election: In the following three elections, one vice-presidential candidate was replaced, one died before the election, and one presidential candidate was almost assassinated.

- Thomas Eaglet

on: In 1972, shortly after Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton was nominated for vice-president by the Democratic Party, it was revealed that Eagleton had suffered from depression in the past and had received electroshock therapy to treat the depression. The decision to place Eagleton on the ticket was done without any of the vetting that typically occurs today, and McGovern offered Eagleton the job in a two minute phone conversation after being turned down by others not interested in running with McGovern. After the disclosure about Eagleton’s depression, McGovern initially pledged that he was behind Eagleton “1,000 percent.” But as questions continued to swirl about Eagleton’s suitability for not only the vice-presidency, but the presidency should he be elevated to that position, McGovern talked with Eagleton’s doctors and concluded Eagleton was too big of a risk, and he was dropped from the ticket and replaced with Sargent Shriver. Because the replacement of Eagleton occurred more than three months before the election, there was plenty of time for ballots to reflect the McGovern-Shriver ticket. McGovern, of course, went on to lose in a landslide to Republican Richard Nixon.

on: In 1972, shortly after Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton was nominated for vice-president by the Democratic Party, it was revealed that Eagleton had suffered from depression in the past and had received electroshock therapy to treat the depression. The decision to place Eagleton on the ticket was done without any of the vetting that typically occurs today, and McGovern offered Eagleton the job in a two minute phone conversation after being turned down by others not interested in running with McGovern. After the disclosure about Eagleton’s depression, McGovern initially pledged that he was behind Eagleton “1,000 percent.” But as questions continued to swirl about Eagleton’s suitability for not only the vice-presidency, but the presidency should he be elevated to that position, McGovern talked with Eagleton’s doctors and concluded Eagleton was too big of a risk, and he was dropped from the ticket and replaced with Sargent Shriver. Because the replacement of Eagleton occurred more than three months before the election, there was plenty of time for ballots to reflect the McGovern-Shriver ticket. McGovern, of course, went on to lose in a landslide to Republican Richard Nixon.

- James Sherman

: In the 1912 presidential election, President William Howard Taft was vying for a second term in the White House against his former friend and predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt (a third party candidate), and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Taft’s vice president, James Sherman died on October 30, just five days before the November 5 election. Taft lost the election in an embarrassing defeat to Wilson, collecting only eight electoral votes from two states (Vermont and Utah) that he won. When the Electoral College met, they chose to cast their vice presidential votes for Columbia University President Nicholas Butler of New York. Given that the ticket of Taft-Sherman lost so decisively, there was no practical electoral impact to his death.

: In the 1912 presidential election, President William Howard Taft was vying for a second term in the White House against his former friend and predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt (a third party candidate), and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Taft’s vice president, James Sherman died on October 30, just five days before the November 5 election. Taft lost the election in an embarrassing defeat to Wilson, collecting only eight electoral votes from two states (Vermont and Utah) that he won. When the Electoral College met, they chose to cast their vice presidential votes for Columbia University President Nicholas Butler of New York. Given that the ticket of Taft-Sherman lost so decisively, there was no practical electoral impact to his death.

- Theodore Roos

evelt: In 1912, Roosevelt was running on the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party ticket against Republican William Howard Taft and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. On October 14, as Roosevelt left a hotel in Milwaukee on his way to give a campaign speech, he was shot at close range in the chest. The bullet was slowed by his metal glasses case and the 50 page folded manuscript of the speech he intended to deliver. Despite the objections of his staff, the Rough Rider insisted on going to the auditorium and delivering his speech. As he stood before the crowd, he said “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot..Fortunately, I had my manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet – there is where the bullet went through – and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.” While he was speaking he had pulled back his vest to show his bloodstained white shirt. He unfolded his bloodied speech, and talked for 90 minutes before finally agreeing to be taken to the hospital. He lived but lost the election to Wilson. Had he died, the Progressive Party would have been tasked with naming a replacement candidate, who would not have fared well in the election, as Roosevelt’s presence on the ticket was very much a personality driven campaign.

evelt: In 1912, Roosevelt was running on the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party ticket against Republican William Howard Taft and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. On October 14, as Roosevelt left a hotel in Milwaukee on his way to give a campaign speech, he was shot at close range in the chest. The bullet was slowed by his metal glasses case and the 50 page folded manuscript of the speech he intended to deliver. Despite the objections of his staff, the Rough Rider insisted on going to the auditorium and delivering his speech. As he stood before the crowd, he said “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot..Fortunately, I had my manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet – there is where the bullet went through – and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.” While he was speaking he had pulled back his vest to show his bloodstained white shirt. He unfolded his bloodied speech, and talked for 90 minutes before finally agreeing to be taken to the hospital. He lived but lost the election to Wilson. Had he died, the Progressive Party would have been tasked with naming a replacement candidate, who would not have fared well in the election, as Roosevelt’s presence on the ticket was very much a personality driven campaign.

After the election: In only one instance has a presidential or vice presidential candidate died after the election but before the Electoral College voted.

Horace Greeley: In the election of 1872, Democrat Horace Greeley, who lost to Republican President Ulysses S. Grant, died on November 29, three weeks after the election but before the Electoral College met to cast their votes. The votes of the six states that Greeley carried were split among four other men. Because Greeley did not win the election, the impact of the Electoral College vote was immaterial in affecting who became president.

Horace Greeley: In the election of 1872, Democrat Horace Greeley, who lost to Republican President Ulysses S. Grant, died on November 29, three weeks after the election but before the Electoral College met to cast their votes. The votes of the six states that Greeley carried were split among four other men. Because Greeley did not win the election, the impact of the Electoral College vote was immaterial in affecting who became president.

President-elect prior to inauguration: In two instances, the President-elect, after selection by the Electoral College was at serious risk of assassination.

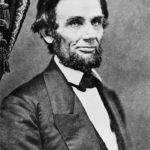

- Abraham Lincoln: A

s President-elect Abraham Lincoln made his way by rail from his home in Springfield, Illinois to take the oath of office in Washington, DC, a plot was uncovered by his security detail of a planned assassination as he passed through Baltimore. Lincoln agreed to change the schedule for when he would pass through Baltimore and was disguised as he transferred trains in the city, foiling the attempted assassination. He was severely criticized for sneaking through Baltimore and into Washington, DC. But had he not changed his plans, it is very likely that he could have been assassinated before his inauguration. Presumably, the Vice President-elect, Hannibal Hamlin would have assumed the presidency, and, of course, history would look very different from what we know today. For an excellent treatment of the attempted assassination, pick up a copy of the book The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War, by Daniel Stashower.

s President-elect Abraham Lincoln made his way by rail from his home in Springfield, Illinois to take the oath of office in Washington, DC, a plot was uncovered by his security detail of a planned assassination as he passed through Baltimore. Lincoln agreed to change the schedule for when he would pass through Baltimore and was disguised as he transferred trains in the city, foiling the attempted assassination. He was severely criticized for sneaking through Baltimore and into Washington, DC. But had he not changed his plans, it is very likely that he could have been assassinated before his inauguration. Presumably, the Vice President-elect, Hannibal Hamlin would have assumed the presidency, and, of course, history would look very different from what we know today. For an excellent treatment of the attempted assassination, pick up a copy of the book The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War, by Daniel Stashower.

- Franklin D.

Roosevelt: On February 15, 1933, just weeks before FDR’s first inauguration during the height of the Depression, the President-elect was riding in an open car in Miami, Florida with the mayor of Chicago. Shots were fired from the crowd. Roosevelt was not hit, but the Chicago mayor, Anton Cermak, was killed and five other people were wounded. Had Roosevelt been assassinated then, presumably the Vice President-elect, John Nance Garner of Texas would have assumed the presidency. Not only would we not have Garner’s colorful phrase that the vice presidency is “not worth a bucket of warm spit,” but America’s emergence from the Depression under FDR’s strong leadership would have developed much differently under the very conservative Garner.

Roosevelt: On February 15, 1933, just weeks before FDR’s first inauguration during the height of the Depression, the President-elect was riding in an open car in Miami, Florida with the mayor of Chicago. Shots were fired from the crowd. Roosevelt was not hit, but the Chicago mayor, Anton Cermak, was killed and five other people were wounded. Had Roosevelt been assassinated then, presumably the Vice President-elect, John Nance Garner of Texas would have assumed the presidency. Not only would we not have Garner’s colorful phrase that the vice presidency is “not worth a bucket of warm spit,” but America’s emergence from the Depression under FDR’s strong leadership would have developed much differently under the very conservative Garner.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

YouTube

YouTube

Pinterest

Pinterest